Biography

the artist's mother

Watercolour 1895

Private collection

British by birth, Walter Percy Day (1878-1965) spent a period in Tunisia as an Orientalist painter before turning to a career in the cinema, first in France, then in England. He was born in Luton (Bedfordshire) to Eli Day and Lucy Day, née Crawley, the eldest of three children (but is unrelated to Lutonian film technician Will Day, as claimed by some cinema historians). From the late nineteen twenties, Day's sons Arthur George Day (1909-1952) and Thomas Sydney Day (1912-1985) worked for their father, Arthur as draughtsman, Thomas as stills photographer and cameraman. From the thirties, Day's stepson, matte shot artist Peter Ellenshaw joined the team as an apprentice. He was therefore universally known to the British film industry as "Pop" or "Poppa" Day and professionally as Percy Day.

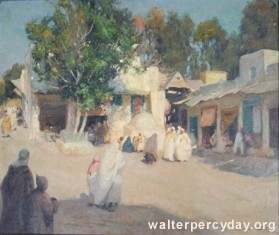

Oil on canvas, 1908

Private collection

The Hazardous Career of an Artist

Hailing from Luton, Eli Day was a craftsman specialised in the manufacture of leather handbags and portmanteaus. A devout Methodist he also served as a lay preacher. Both sides of the Day family were involved in making the boaters fashionable in the Victorian era, the straw hat industry then being based in Luton. As his watercolour portrait of his mother reveals, Percy was already a gifted painter by his late teens, with a talent for penetrating psychological insights of his sitter. At the age of fifteen, his parents apprenticed him to his cousin, William J. Roberts, a Luton-based photographer, training which proved to be invaluable for his future career. He also attended the Heatherley's Art School, in London, an academy specialised in figurative painting and in 1901 won a scholarship to the Royal Academy School of Art which he attended until 1905.

Graduates of the Royal Academy were formerly expected to complete their education by a European Grand Tour, in order to absorb the Greco-Roman culture on which their training was based. By the time Day graduated, however, the sites of classical Greece and Rome had been replaced by the Oriental destinations appropriate to painters of the Orientalist school. In 1907 Day accordingly embarked for Tunisia and lived for five years in the coastal village of Sidi Bou Saïd, home to an important artists colony. As a result, Day's first works are Orientalist in style. Following an exhibition of fifty pictures at the Grand Hotel, Tunis, in 1910, he was invited to join the Tunisian Salon.

Oil on canvas, 1910

Private collection

While in Tunisia, Day married his childhood sweetheart, Ada Chandler, who hailed, as he did from Luton. Their son Arthur was born there and she was pregnant with Thomas when an outbreak of political unrest decided the family to return to England. Percy took a studio in Saint John's Wood, in the grounds of the home of Professor Augustus-Désiré Waller, a professor of physiology at London University. Among the influential sitters he painted at this time was the industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (Wardown Park Museum, Luton). He also participated in exhibitions at the Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts, the Walter Art Gallery in Liverpool and at the annual retrospectives organised by the Royal Academy.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Day attempted to enlist, but was turned down on medical grounds. He was assigned to an aircraft factory, where he directed design department for the duration of the war, during which his elder brother, William, died in action in 1916. The war over, he resumed his profession. A picture entitled The Eleventh Hour of the Eleventh Day of the Eleventh Month, 1918 (Preston Art Gallery) hung on the line at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1919, caused a considerable stir in the press. But many of his wealthy sitters had departed precipitately for the war, never to return. With two young sons to raise, the painter was obliged to find other sources of revenue. It was while he was painting the portrait of the Chairman of the Elder Dempster steamship line, that his sitter casually asked if he had thought of augmenting his income by working for the cinema; Mr. Gurney provided the necessary introductions.

From Canvas to Glass

Oil on canvas, 1911

Private collection

Day was hired by Ideal Films in Borehamwood, near Elstree, in 1919. Here he was initiated into the art of visual effects techniques, first mastering the glass shot and the Hall process. Such sleights of hand can trick the spectator into believing that the actors are tramping through a jungle, participating in historic events or involved in cliffhanging situations when in fact the crew has never of course quit the studio lot.

The glass shot was invented by the American cinematographer, Norman Dawn, in about 1905. Sheets of glass three or four metres wide were mounted on the floor of the studio, or on location, as the case may be, in front of the camera. The décor was painted directly onto the glass, leaving a gap through which the live-action footage was filmed, in one pass. The inherent drawback of the glass shot was that it was uneconomic, since the painting had to be completed on the set, which meant that shooting was held up until the work was finished.

The Hall process was patented in 1921 by Walter G. Hall, an English-born set designer active in Hollywood. It consisted of mounting consisted of painting small-scale perspective pictures onto composition board, cut out and mounted, the bevelled edges away from the face, in the foreground between the camera and the set. The advantage of this technique was that it did away with the reflections inherent to the use of glass.

As luck would have it, at the time Day joined the Elstree studios, the British movie industry was suffering an eclipse. The French film industry, on the other hand, was booming which encouraged Day to emigrate there, in 1922. Working primarily for the studios in Epinay and Joinville from his home in Montmorency (Oise), one of his early assignments was André Hugon's L'arriviste, released in 1924. The film was a source of consternation to the French political establishment, causing an angry member of parliament to table the motion: "How had a foreigner obtained the authorisation to film this house?" Without ever setting foot inside the house, Day had reproduced the interiors of the Chambre des Députés, so accurately that the illusion had fooled even the members themselves. As a result, he was deluged with commissions. During he twenties, Day created trick shots for such luminaries as Jean Renoir, Raymond Bernard, Julien Duvivier, and Abel Gance among others.

The most celebrated French film of the twenties was Abel Gance's Napoléon et la révolution, a silent film released in 1927. One of three special effects designers assigned to the film, Day painted the glass shot of the Club des Cordeliers, and in addition played a bit part in the film, namely the rôle of Admiral Hood, the British general defeated by Napoléon at Toulon. By an irony of fate, this masterpiece has since been reconstituted by Kevin Brownlow - an Englishman.

While still resident in France, the Elstree studios commissioned Day to shoot the visual effects for a British silent, Alfred Hitchcock's The Ring (1927). For this film, he learned the Schüfftan shot, a process which involves the use of a scale model and a mirror. He was trained directly by the inventor Eugene Shüfftan, who was invited over from Germany by the British studio. By angling the mirror at forty-five degrees, it was possible to reflect a miniature or a painting, or a photograph, and to superimpose it over the live action set, seen through the clear proportions of the glass. A Schüfftan shot was used for the boxing ring scene at the Albert Hall, the first British film in which this process was used.

The Stationary Matte

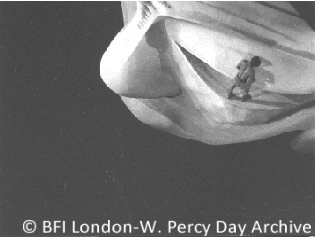

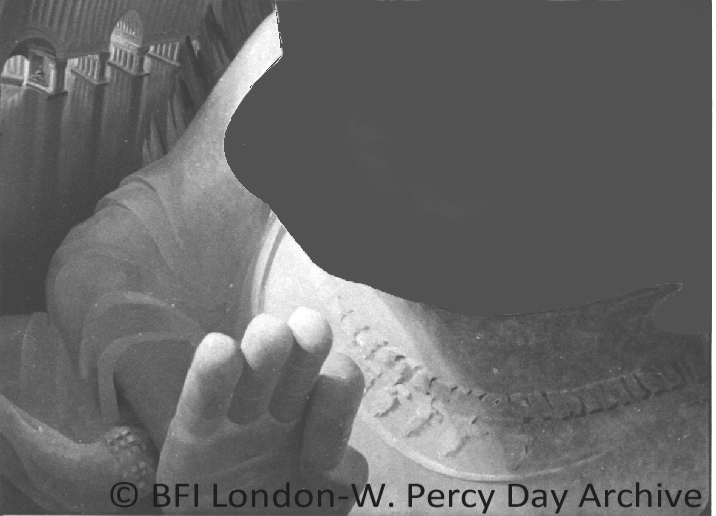

Thief of Bagdad

(1940)

© BFI London-W. Percy Day Archive

with area to be painted matted out

to be superimposed on the film

Having been trained as a photographer, Day had already given some thought to the idea of using mattes instead of glass while still at Elstree. When he dared to suggest to the powers that be at the studio that there might be a more innovative method for obtaining the same results, he wryly noted that "I nearly went out on my ear for doing so". During the shooting of Julien Duvivier's classic, Au Bonheur des Dames (1929), based on Emile Zola's novel, Day finally was given the opportunity to put his own ideas on matte painting into practice. Filming the exterior façades of the department store proved to be an insurmountable difficulty, since the cameraman could not distance himself sufficiently from the buildings, hedged in as they are by narrow streets, to shoot an overall and for safety reasons, it was out of the question to mount a 4 metre wide sheet of glass on a busy main boulevard.

The stationary matte, dubbed the Day process in France, was not however an entirely new concept. The technique was already familiar to matte artists associated with the American studios, who joined with matte artist Ferdinand Pinney Earl in a legal battle to prevent Dawn from exercising his rights to exploit a similar process which he had patented in June 1918. Even though "matte shot" is now the universally accepted term, Day did not care for it and preferred the term "process shot". Until it was superseded by the computer, matte painting remained a mainstay of the visual effects teams' repertoire.

The stationary matte did away with the need for mounting sheets of glass on the set or outside. Areas of the frame at the top and sides were first masked off with black card placed in front of the lens. After the take, a few feet of test shot were reserved and the rest of the footage was stored away for future use. The test film was projected onto a glass pane mounted in the painter's studio, and the missing sections were painted in, in accordance with the sketches provided by the art director. Once the matte painting was finished, the exposed film was reloaded into the camera, the parts already exposed were masked off with black cardboard, and the painting double exposed onto the live footage. The economic advantages of the stationary matte to the film industry were enormous. The process freed the crew to continue shooting while the matte artist worked in his studio (thereby reducing the number of trips on location, much to the dismay of film crews).

Day's newfound glory was alas shortlived. The screening of the first talkie some six months later sounded the death knell of the silent film era. The stationary matte worked perfectly on the silent movie camera, but the vibration caused by the André Debrie sound movie camera caused the matte shots to be out of focus.

Black Narcissus

(1947)

© BFI London-W. Percy Day Archive

matted out

superimposed over film

A Career with Korda

Thanks to a recommendation from the artist's friend, lighting cameraman Georges Périnal (of Marius fame) who was based with Korda's unit in Paris, the Hungarian director commissioned Day to paint the matte shots for The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). The painter noticed that Korda did not seem unduly perturbed by the "jiggle" problem. With good reason: his studio was equipped with the new American Bell and Howell camera, which was equipped with fixity pins. An international hit starring Charles Laughton, The Private Life of Henry VIII set the British film industry back on the map.

In 1932, Pop Day returned to England, moving into a cottage in the village of Iver (Buckinghamshire), near the Elstree studios. In his autobiography, Peter Ellenshaw has left a vivid impression of his first meeting with Day. The encounter was significant in more ways than one, since it was instrumental in bringing together Peter's mother Adeline and Percy Day, who by this time was a widower.

From 1936, Day directed the matte department at Denham Studios, the state-of-the art studio founded by Korda. In addition to the flamboyant Hungarian, Day worked with his stable of upcoming young directors, including Anthony Asquith, William Cameron Menzies, David Lean and Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger. The Spy in Black heralded the start of a long period of collaboration with The Archers. The artist's irascible temperament did not prevent Powell from rendering him an affectionate homage in his autobiography, in which he saluted him as one of the greatest moviemakers I have ever known. For The Drum, one of two colour films Korda's released in 1938, Day adapted the matte shot to Technicolor, subsequently perfecting the process the with the aid of the late Douglas Hague.

In 1939, Alexander Korda Productions commenced work on the now celebrated Thief of Bagdad. The shooting of this classic, punctuated by changes of director and the outbreak of the Second World War was fraught with drama from start to finish. Korda was determined to exploit the visual effects to a maximum, through the virtuosity his art director Vincent Korda and special effects director Lawrence Butler assisted by Poppa Day (one of four associate art directors). Among the memorable special effects sequences created by Day and sons were the flying horse which gallops off with the Caliph into the sky, the flying carpet on which Sabu makes a spectacular escape from a tent, and the quest for the all-seeing eye in the idol's head. Panned by contemporary critics, who carped that the film focused too much on the visual effects, the film has nevertheless withstood the test of time and is now standard fare on Christmas television.

The Consequences of World War II

The Second World War brought Poppa Day's collaboration with his sons to an end. Arthur was posted to Libya with the Film and Photographic Unit of the 8th Army where he served as a "Desert Rat" under Field Marshall Montgomery. Thomas was assigned to the Cinematographic Unit of the army and spent the duration of the war in Britain, making propaganda and training films in Wales and Scotland. Peter enlisted as a pilot in the Royal Air Force and ultimately settled in California, where he became an Art Director for Walt Disney. Poppa Day remained at Denham Studios until 1946, when he joined Korda at Shepperton Studios as Director of Special Effects.

One of the important objectives of the British government during the war, was to boost the morale of the beleaguered British people and to exploit the medium of film as a propaganda tool. The film studios were encouraged to make heroic war epics such as 49th Parallel (Powell & Pressburger) and In Which We Serve, (Noël Coward and David Lean) and The First of the Few (Leslie Howard). As Day did the mattes and special effects for these productions, it was probably during the shooting of the latter that he painted Howard's portrait (present whereabouts unknown).

Agincourt battle scene painted on glass

Private collection

Apart from the Thief of Bagdad, Day worked on numerous classics released during the forties. They include Powell & Pressburger's controversial The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp; I Know Where I'm Going! and Sir Laurence Olivier's magistral production of Henry V, adapted from Shakespeare's play. Day was reticent about revealing his secrets, according to film critic Egon Larsen, who interviewed him for the article "The Magician of British Cinema". It is through the director's memoirs that we learn about the difficulties involved in creating the famous whirlpool scene in I Know Where I'm Going! Powell relates in detail how Day invented the whirlpool, made from a plastic resembling gelatine. For the Battle of Agincourt in Henry V, he made the horses' heads move and the pennants flutter in the wind. It was probably during the shooting of this film the artist painted the portrait of the inimitable "Larry" (present whereabouts unknown).

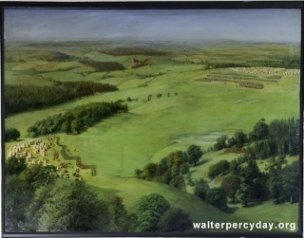

In a recent poll organised by The Times newspaper (4 August 2005) Black Narcissus (1947) was voted the best British film of all time. Adapted from the novel by Rumer Godden by Powell and Pressburger, it relates the attempt by Catholic nuns to found a charitable institution in the Himalayas. It amused Powell that some spectators claimed that they knew the precise location where the film was shot. Wrong! The entire film was shot on the Pinewood Studios back lot, the mountain scenery being entirely the work of Poppa Day, assisted by Ellenshaw. Jack Cardiff was awarded an Oscar for the colour photography, but wondered ruefully in his memoirs whether he would have got the Oscar if they had known Poppa Day had painted the beautiful matte shots! The painter was not so honoured by the film industry, but his work did not go unnoticed for a year after the film was released, he was awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire) for his services to the British film industry.

An Eternal Emigré

WPD retired officially in 1954 at the age seventy-six but continued to work in an advisory capacity for the studios. He and his wife moved to Kent, when he took up painting in earnest again. A self-portrait hung on the line in 1954 at the Royal Academy earned him a gold medal. However, as his children had all emigrated to the other side of the Atlantic, the couple decided in 1959 to follow them. They first joined Thomas and his family in a brief lived venture at Montego Bay, Jamaica before moving from there to California to live near the Ellenshaws. Pop Day died on 20 May 1965, in Los Angeles.

Day could be said to be fortunate in having received official recognition for his cinematographic achievements during his lifetime. Thanks to the promotional work of institutions such the National Film Theatre, the Institut Lumière and the Cinémathèque, interest in classic films has revived and is alive and well today. Modern technology has made movies accessible to a wide spectrum of the public via the medium of DVD and television. Would he have been happy? I doubt it. Firstly, he would have been surprised to learn that his posthumous claim to fame stemmed from his innovations in the realm of visual effects. While he would have certainly been gratified to know that his name is inscribed in the annals of Le Septième Art, he would have undoubtedly preferred for his name to have passed into posterity a painter. He would have harrumphed dismissively, arguing that film was not art, but mere ephemeral entertainment, and have relegated his accomplishments to that of a technician. Day was unfortunate in living in an age which corresponded to the rise of modern schools of painting and the rejection of traditional academic canons. The knowledge that his pictures are now collectors' items would have afforded him much greater pleasure.

Susan Day

Acknowledgements:

Warm thanks to Lenny Borger, Jim Danforth, Luigi Durante and Anne Regourd for their expertise, help and advice.